Gyrotron Well Drilling for Deep Geothermal Energy

Bit-less deep-well drilling teases the prospect of terawatts of clean energy.

Recently1, we wrote about the potential to obtain large amounts of low-carbon energy from the heat of the Earth at temperatures found at depths readily reachable by conventional drilling methods, which is about 3 km (1.8 miles).

The Earth is deeper than that, obviously, and it just keeps getting hotter the deeper you go, at an average rate of 25° to 30° C per km (roughly 80° F per mile). At 20 km (12 miles) depth, the temperature is as high as 600° C (roughly 1100° F), although it varies widely depending on the underlying geology. Temperature that high means seriously useful heat for all sorts of purposes ... if you can reach it.

How much heat is down there?

The heat content of the entire earth’s crust (the upper lithosphere, 20 to 65 km deep in continental areas) has been estimated at 5.4 x 1014 TJ (terajoules)2, an impossible number to visualize, but, for context, that’s about 8 million times more energy than the world’s economy consumed in 2024.3

In our first article about geothermal, we didn’t talk about the potential harvestable energy of the deep crustal zone beyond about 3 kilometres. Those depths have effectively been unreachable in the past, because conventional drill bits take a long time to actually drill at high temperatures, they tend to break down, and pulling up the drill strings to change bits takes longer the deeper you get.

That looks about to change.

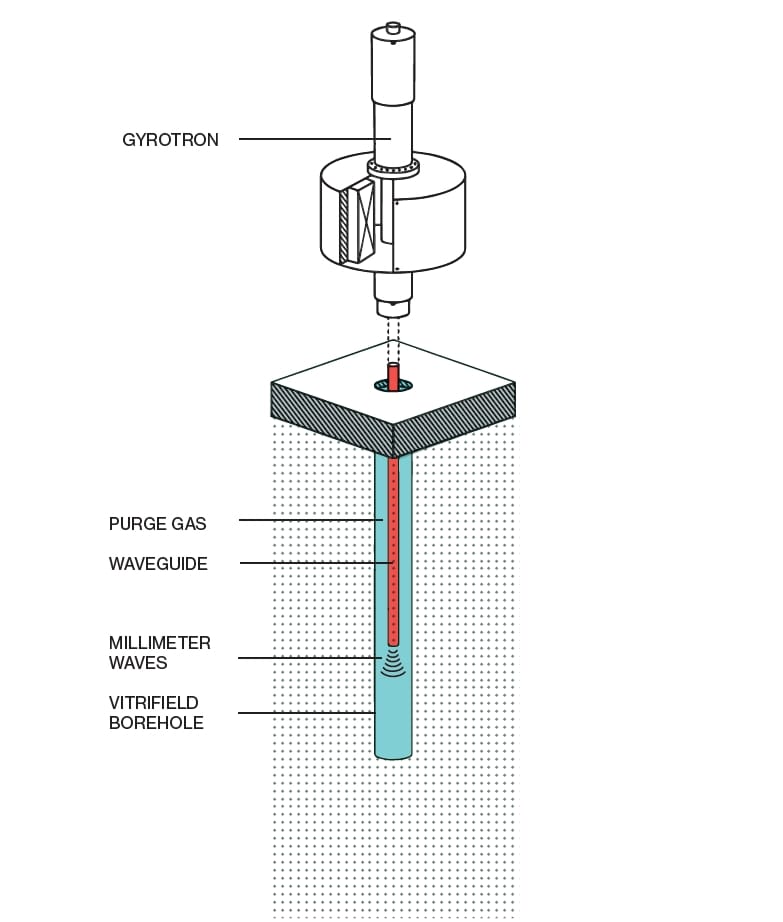

For over 15 years, scientists at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) investigated a different way of drilling, using a device called a gyrotron, which can be thought of as a kind of high-power, open-ended microwave oven.4 The technology has long been familiar in the nuclear fusion world.

The idea here is to blast enough energy into the rock to heat it to the point of vitrification and disintegration. The microwaves in our countertop ovens operate at a compromise frequency between penetrating power and the resonant frequencies of water and other molecules in food. The molecules that make up granite and basalt (the two most common crustal rock types) have different resonant frequencies, and gyrotrons operate at a frequency 40 times higher than a kitchen microwave, and very much shorter wavelengths, referred to as millimetre waves.

The technology was spun off seven years ago from MIT to a company called Quaise Energy. In the last year, the company has taken the technology from the lab to the field. This summer they completed a demonstration well 118 metres (390 feet) deep into granite. This video provides a high-level explanation of the how the drilling technology works. Quaise believes the technology will allow drilling to a depth of 20 km.

An extensive interview of Quaise Energy CEO Carlos Araque by the volts.wtf podcast provides a pretty deep dive (at least for us non-geologists) into the physics, the geology, the technology, and the business case for harvesting deep geothermal energy by gyrotron.5 We won’t go into detail on all the areas covered in the interview, but several key points stand out for us:

- The gyrotron itself stays at the top of the well and doesn’t have to be lowered to the bottom

- The energy used to operate a gyrotron drill is about the same required to operate a regular oil or gas drill rig

- The quantity of heat contained in rock at 20 km, where it is 600° C and under very high pressure, means that water used to extract the heat would return at a supercritical condition, typical conditions of boilers and turbines in thermal power plants

- Water to extract the heat would circulate in a loop, not be discarded

- Geothermal wells could potentially be deployed anywhere (depending on the specific conditions found at depth), including replacing fossil-fuel heat sources in thermal power plants

- Wells would have a working life of decades before they got too cool, and would naturally re-charge as heat soaks back in to the well from the surrounding rock

- The EROI (energy returned on energy invested)6 has the potential to be significantly higher than fossil fuels

As a next step, Quaise Energy is building a much larger geothermal plant in central Oregon, which will produce about 50 GW (gigawatts) of energy, relying on wells drilled to about 4 km (~2.5 miles) using the gyrotron drill.7

While the company’s ambition is huge, we suspect scaling up the drilling from a 118 metre well to a 4 km well may encounter unforeseen engineering challenges, and scaling up beyond, to a 20 kilometre well, may present even more challenges. We can’t know whether those challenges will be successfully overcome but the potential is enormous.

This is a technology to watch.

Reading

- https://www.sweetlightning.eco/dr/

- ResearchGate. “(PDF) The Possible Role and Contribution of Geothermal Energy to the Mitigation of Climate Change.” Accessed December 18, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284685252_The_possible_role_and_contribution_of_geothermal_energy_to_the_mitigation_of_climate_change.

- Our World in Data. “Global Primary Energy Consumption by Source.” Accessed December 18, 2025. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-energy-substitution?country=~OWID_WRL.

- “MIT Spinout Quaise Energy: Working to Create Geothermal Wells Made from the Deepest Holes in the World.” Main, January 25, 2023. https://energy.mit.edu/news/mit-spinout-quaise-energy-working-to-create-geothermal-wells-made-from-the-deepest-holes-in-the-world/.

- Roberts, David. “Volts | David Roberts | Substack.” August 15, 2025. https://www.volts.wtf/.

- https://www.sweetlightning.eco/rtg-eroi-and-the-net-energy-cliff/

- “Stanford Geothermal Workshop Abstract.” Accessed December 20, 2025. https://pangea.stanford.edu/ERE/db/GeoConf/Abstract.php?PaperID=9354.