Elastocaloric Cooling

Cool new tech for refrigeration without refrigerants or compressors.

What’s this — the latest celebrity-touted health fad?

Sorry to disappoint. Elastocaloric cooling is an obscure, but previously impractical, technical phenomenon that’s been around awhile. Recent progress may make it an important tool in the climate change struggle.

Let’s look first at why cooling matters.

Global demand for refrigeration (cooling, air-conditioning, and freezing) is growing as the world warms, with an estimated 430 million units being sold annually by 2030. The sector is a significant contributor to climate change, currently accounting for about 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions.1

Most of this cooling is accomplished with vapour-compression machines that chill the air or water being cooled by exploiting the latent heat of evaporation of some liquid chemical (known as a refrigerant), then compressing the resulting hot gas, and finally rejecting the extracted heat to the surroundings. This is why your fridge blows hot air out the back or bottom. Different refrigerants have different boiling points, which match the temperature needed for the cooling or freezing application.

Refrigeration processes produce greenhouse gases in two ways. The first and largest contributor (about two thirds), is the electricity used to run the compressors. The second is through leakage of the refrigerants, which have huge global warming potential (GWP), into the atmosphere.

Most of the work in the past to reduce refrigeration’s GHG impact has focused on reducing leaks, improving efficiency of the vapour compression cycle, and developing refrigerants with low global warming potential.

But what if you could eliminate refrigerants and the vapour-compression cycle altogether?

One such cooling mechanism that needs no moving parts has been around for some time. You may even have encountered it in the form of some kinds of 12V portable coolers. These devices work via the Peltier effect, which is essentially a thermocouple (a temperature sensor consisting of two dissimilar metals that produces a voltage as the temperature changes) that is run backwards – electric current in produces cold out of one side and heat out the other. Peltier effect coolers are inefficient, expensive, and do not produce big temperature differences.

Elastocaloric cooling is different. It relies on a set of remarkable metal alloys called shape memory alloys (SMAs). SMAs contain two different crystalline structures, in proportions that depend on temperature. The crystalline structures undergo a solid-state phase change from one to the other as they cool or warm, so that SMAs effectively “remember” the shape they were at the opposite temperature. The shape differences are big enough and produce enough force that SMAs have been used in such widespread applications as fasteners, sensors, medical devices, and the arms that hold the solar panels of the Hubble space telescope.

Now, the cool thing (pun intended) about shape memory alloys is that the effect also works in the other direction, that is, if you change the shape by applying an external force to an SMA it gives off heat, then when you release the force, it absorbs heat. When used for cooling, that heat-absorbing property is called elastocaloric cooling.2

Until recently, elastocaloric cooling did not produce low temperatures and was difficult to scale up. Recent advances have changed that.

Researchers have developed a new shape-memory alloy that cools from room temperature (24° C) down to -12° C.3 That’s cold enough for a freezer, making it suitable for commercial application. Others have found configurations that allow for scaling-up capacity.4

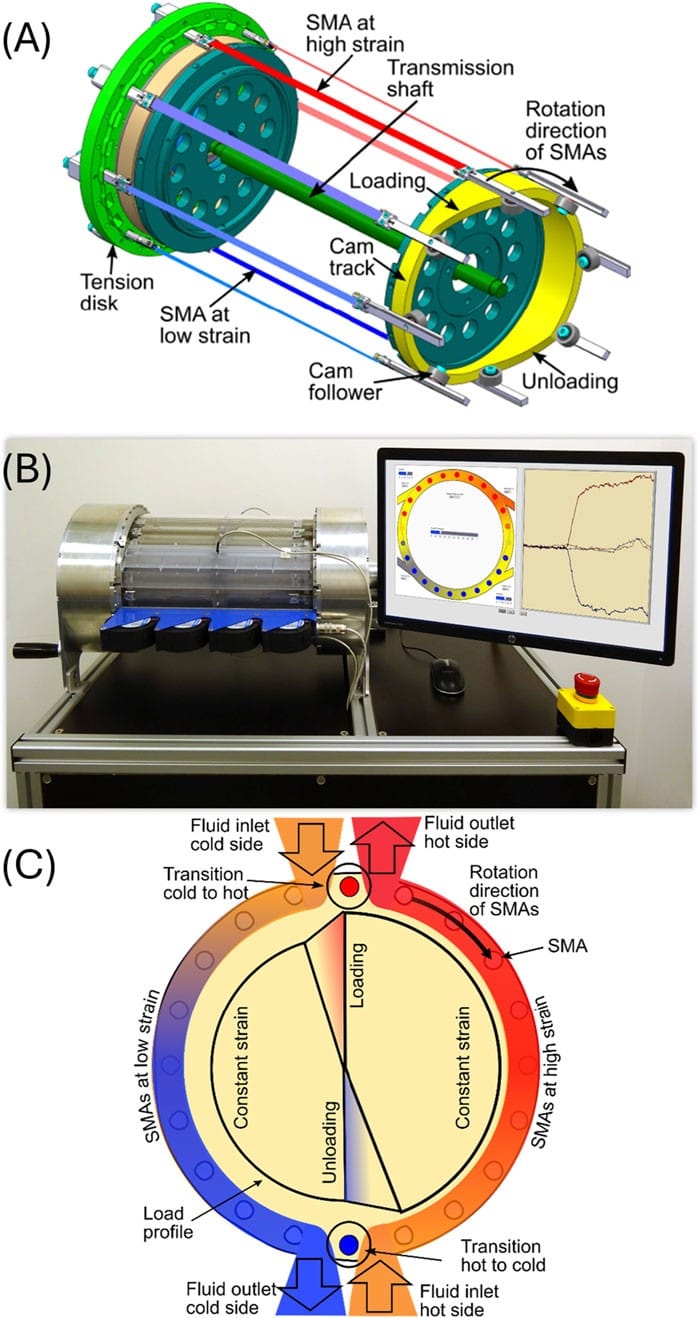

Here are schematics and a photo of a desktop-scale working demonstrator of an SMA cooler:

The SMAs in this demonstrator are thin bands that are alternately stretched and relaxed as the device rotates (top graphic, A), with one working fluid being cooled by the device in order to do the refrigerating, and another working fluid taking away the removed heat (bottom graphic, C).

The energy efficiency of the best of these working prototypes is beginning to approach that of good vapour-compression machines, with COP (coefficient of performance, a ratio of cooling power out vs input power, larger is better) as high as four, compared to five-plus for traditional machines.5

While we can’t yet beat commercial elastocaloric coolers, enough working prototypes and demonstrators exist6 to suggest that this technology is on the verge of coming of age7, perhaps signalling the beginning of the end of vapour-compression cooling.

Reading

- Refrigerants methodology version July 2022.pdf, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-07/Refrigerants%20methodology%20version%20July%202022.pdf Accessed 2026-01-29

- Wang, Yao, Ye Liu, Shijie Xu, Guoqu Zhou, Jianlin Yu, and Suxin Qian. “Towards Practical Elastocaloric Cooling.” Communications Engineering 2 (November 2023): 79. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-023-00129-5.

- Zhou, Guoan, Zexi Li, Zhongzheng Deng, et al. “Sub-Zero Celsius Elastocaloric Cooling via Low-Transition-Temperature Alloys.” Nature 649, no. 8098 (2026): 879–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09946-4.

- “World’s 1st Kilowatt Cooling Tech Brings Rooms to 70°F in 15 Minutes.” Accessed January 30, 2026. https://interestingengineering.com/innovation/zero-emission-elastocaloric-cooling-system.

- Li, Xueshi, Peng Hua, and Qingping Sun. “Continuous and Efficient Elastocaloric Air Cooling by Coil-Bending.” Nature Communications 14, no. 1 (2023): 7982. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43611-6.

- Kirsch, S. M., Welsch, F., Michaelis, N., Schmidt, M., Schütze, A., and Seelecke, S. (2018b). Continuously operating elastocaloric cooling device based on shape memory alloys. Darmstadt, Germany: Development and Realization - Poster, 16–20.

- Ehl, L., N. Scherer, D. Zimmermann, et al. “Elastocaloric Can Cooler: An Exemplary Technology Transfer to Use Case Application.” Frontiers in Materials 12 (March 2025). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2025.1563997.