Extinction Exits

How species get out of deep trouble. Part 2 of a series on extinction.

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge and shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things....

— Gerard Manley Hopkins, "God's Grandeur", 1877

Threatened species can "come back"

If you saw our recent article, The Long Way Home, you have a rough idea of one way humanity keeps track of threatened species: the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) Red List.

The Red List of species is sorted into different categories of endangerment.1 The list can be daunting. Just looking at it can be uncomfortable because of its implications: a large number of species are in trouble now or will be soon.

How many? Broader scientific estimates by the United Nations2 and others suggest that the actual number is perhaps a million or more. Certainly several hundred thousand.

In spite of this, The Red List does offer grounds for optimism, too. Each year, some species improve their positions on the list, coming back from its "dire" categories: extinct, extinct in the wild, critically endangered, and endangered. The names of improving species move "down" the list, from more-threatened to less-threatened.3, 4, 5

Top four escape routes

When a species moves down the list, predictable things happen: populations grow, threats lessen, the genetic pool increases and diversifies, and habitats become more hospitable. Here are some of the mechanisms.

#1: Broad conservation efforts

Sometimes, for one reason or another, under international, national, regional, or private authority, habitats are protected and restored. The techniques vary and are often applied in concert:

- Re-wilding or reforestation

- Removal of invasive species

- Improved predator/prey balance

- Restored vegetative food stocks or prey species

See, for example, our article More Fish in the Sea, which examines how marine protected areas (MPAs) can benefit all species within a region. Like any nature preserve, MPAs work quite well when they are properly done.

Here's a good example of how broad conservation efforts can benefit a single species. In the early 2000s, the Iberian Lynx was red-listed as critically endangered; counts showed fewer than 100 cats. But after two decades of broad conservation efforts, including community engagement, translocation, habitat restoration, and repopulation of important prey species (yum, rabbits!), the lynx count is up to 2,000. The species has been downlisted to vulnerable status on the Red List.6

#2: Directed rescue efforts

Often, efforts are focused specifically on a particular species or group of species, with less attention paid to the general environment and surrounding habitats. Typical efforts include:

- Threat reduction

- Captive breeding

- Population re-introduction (sometimes from a geographically isolated population to a depleted one)

- Education

- Advocacy

- Lobbying

- Trade restrictions

- Anti-poaching laws

- Hunting and fishing bans (see How Not To Be a Boiled Frog to read about the collapse of the North American Atlantic cod stocks, among other things)

For instance, the awe-inspiring humpback whale was at one time considered vulnerable, but a worldwide ban on commercial whaling in 1986, special marine protected areas like the Hawaiian Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, and legal protection under laws such as Canada's Marine Mammal Protection Act or the U.S. Endangered Species Act have significantly lowered threats from human hunting. Humpbacks are now a species of least concern.7

#3: Natural population recovery

At-risk populations can rebound without any human intervention at all. For reasons we don't control, something changes:

- Competition reduces

- Environments change

- Disease outbreaks wane

- Predators decline

- Habitats naturally regenerate

- Isolated habitats connect and combine breeding populations

- Species under pressure can "evolve out" from underneath the pressure of a novel stressor

The Guadaloupe junco8 was Red-Listed as endangered in 2016. Feral goats were destroying its habitat, and feral cats were assaulting its population. When deliberate elimination of the goats caused rapid regrowth of the natural habitat, the junco population began to grow, too. Today, they are Red-Listed as vulnerable. While their numbers continue to rise, the cats are still a problem.

#4: Accidental recovery

Species can recover on their own, without any intentional assistance from people. Humans can withdraw from a geographic area, sometimes due to shifts in policy or economy. Wherever farmland is abandoned or natural regrowth takes off, species opportunistically will find a toe-hold (or wing- or root-hold).

In the large Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, the fascinating Przewalski's horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), once classified as extinct in the wild, is now "merely" endangered. Much of this improvement is due to intentional breeding and conservation programs, but the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone has provided an unintentional refuge, free from human pressures, where the deliberately re-introduced horses can thrive.

The Korean DMZ (demilitarized zone), created in 1953, is a 4 kilometre by 250 kilometre strip that runs along the 38th parallel. It has largely been abandoned by people, which has created an opportunity for thousands of local species, including the critically-endangered Amur leopard10 and the endangered red-crowned crane11.

Downlisted species usually improve for complex reasons

Of course, real-world conservation is nuanced and difficult. While identifying these paths separately helps us understand how conservation works, when species are downlisted, they usually have benefited from more than one escape route. Whatever combination of conservation measures can help a species is usually brought to bear.

A parting cause for celebration, and an illustration of the complex and nuanced mechanics of recovery: the green sea turtle, once listed as endangered, had its status in the 2025 Red List quite dramatically changed to "least concern". This stupendous effort took decades. It was a collaboration between many different agencies, companies, and concerned citizens.

It wasn't easy, but it worked. Spectacularly.12

Special Note

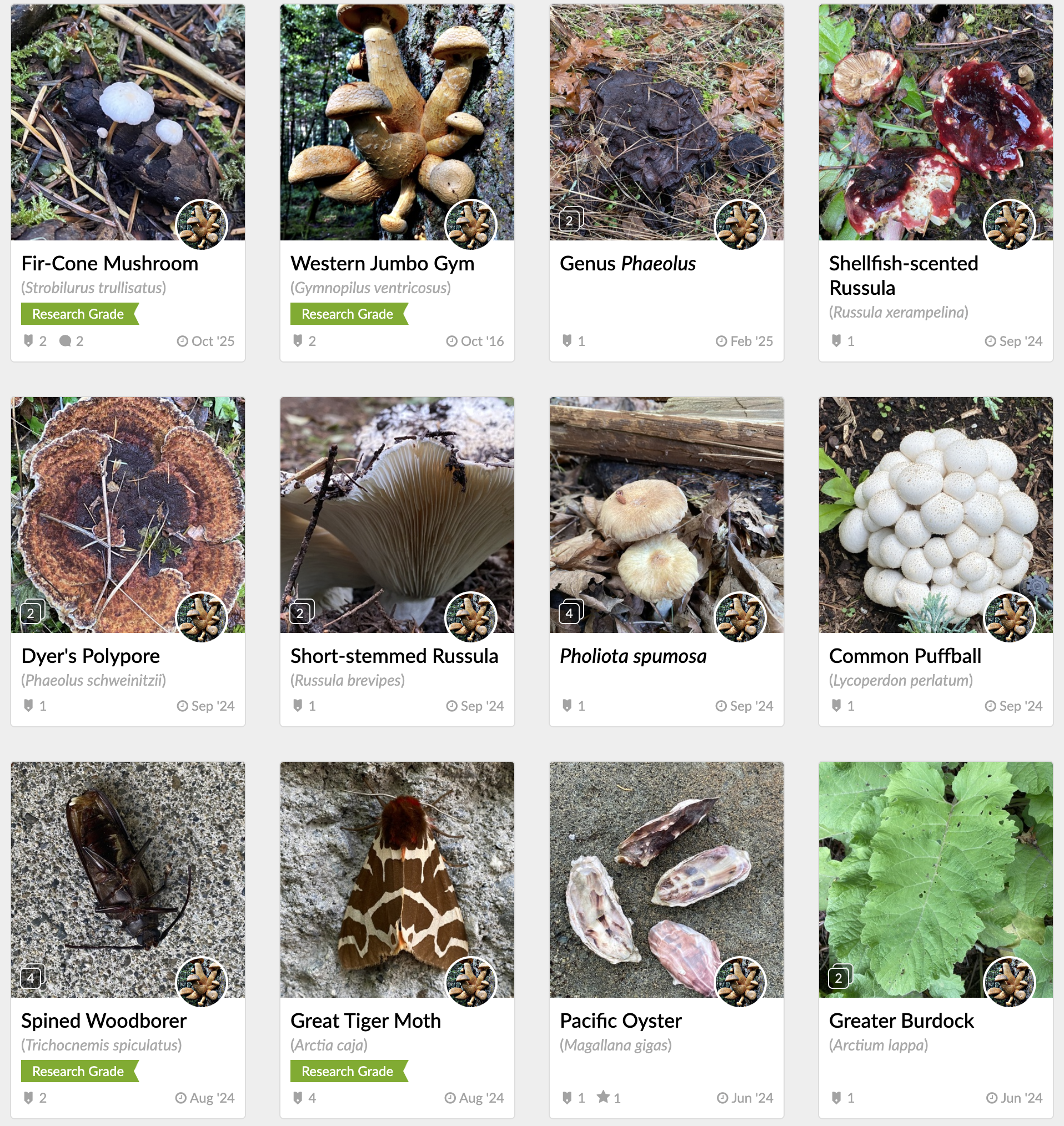

Take some time to follow the links to the downlisted species referred to in this article. Most of the links are to pages on iNaturalist.org. It's one of the best citizen-science sites, and both a wonderful aid to discovering the names and profiles of nearly any species you could find and a tool used by professionals for species counts and biodiversity research.

Don't be surprised when a world expert helps you figure out the species of that funny little red bird in your yard.

A peek inside iNaturalist:

Reading

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. n.d. “The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.” Accessed October 20, 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). "Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Summary for Policymakers." IPBES Secretariat, 2019. https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment.

- Betts, Matthew G., et al. "A framework for evaluating the impact of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species." Conservation Biology 34, no. 4 (2020): 871–881. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13454.

- Butchart, Stuart H.M., et al. "Improvements to the Red List Index." PLOS One 2, no. 1 (2007): e140. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000140.

- Simkins, A.T., et al. "Past conservation efforts reveal which actions lead to positive Red List status changes." Conservation Letters 18, no. 2 (2025): e12900. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12900.

- Simkins, A.T., et al. "Past conservation efforts reveal which actions lead to positive Red List status changes." Conservation Letters 18, no. 2 (2025): e12900. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12900.

- Baker, C. S., et al. "Embracing conservation success of recovering humpback whales: the case for delisting the North Pacific population under the U.S. Endangered Species Act." Marine Mammal Science 32, no. 2 (2016): 485-499.

- Friis, Gunnhild, and Borja Milá. “Change in Sexual Signalling Traits Outruns Morphological Divergence across an Ecological Gradient in the Post‐Glacial Radiation of the Songbird Genus Junco.” Evolution 74, no. 9 (2020): 2106–2122.

- Brady, Linda M. "From war zone to biosphere reserve: the Korean DMZ as a scientific landscape." Interface Focus 11, no. 3 (2021): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2020.0023.

- Li, Hailong, Yebin Xia, Yuanyuan Qiao, Lingyun Zhou, and Yu Tian. "Transboundary Cooperation in the Tumen River Basin Is the Key to Amur Leopard (Panthera pardus) Population Recovery in the Korean Peninsula." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1 (2023): 1–18.

- Lee, Sang Don, and Jae Hyun Kim. "Wintering Habitat Use Pattern of Red-Crowned Cranes in the Demilitarized Zone, Korea." Journal of Ecology and Environment 42 (2018): 25.

- Santana, Pedro M. dos Santos, et al. "Review Conservation of sea turtles in scientific literature." Ocean & Coastal Management 228 (2022): 106333. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0964567722003562.