Torque wars

Electric motors make a comeback.

Click on the icon below to hear an audio version of this article:

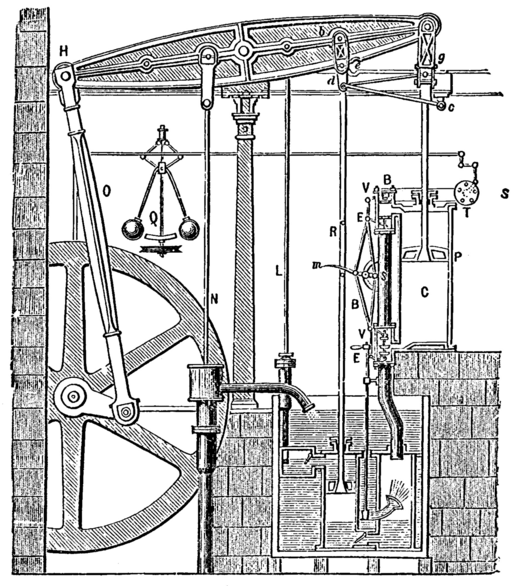

It started a long time ago with James Watt. I am sure that Watt did not intend to start a war that would rage for more than a century, but in the arena of unintended consequences, it was a big one. Watt’s innovations to the external-combustion steam engine marked the beginning of what we might call the torque wars — a long competition to determine the dominant engine or motor to power the modern world.

To our knowledge, no one died fighting this war, although with inventions of this scale there were likely casualties along the way. Watt’s engine used a coal- or wood-fired boiler to heat water and produce steam. That steam was cleverly applied to a piston, converting back-and-forth motion into rotation. While Watt himself did not build the first steam locomotive, his work laid the foundation for steam-powered transportation — and, accidentally, for the torque wars.¹

Back to school for a moment. What we are really talking about here is torque: a force applied in a way that causes rotation. Torque is measured in pound-feet (lb-ft) or newton-meters (N·m) — interestingly, a combination of force and distance.

The easiest way to understand torque is with a stubborn, rusty nut. Suppose you start with a 3-inch wrench. You apply roughly 200 pounds of force and … nothing happens. Back to the garage you go, returning with a two-foot wrench. Apply the same force and the nut comes off easily — saving you a trip for a cutting torch. In the first case, you applied about 50 lb-ft of torque (0.25 ft × 200 lb). In the second, you applied 400 lb-ft — eight times more torque.

Powering things that rotate — wheels, gears, propellers — quite literally moves the modern world. It is not an exaggeration to say that without torque, modern civilization as we know it would not be possible.

Throughout the 1800s, a series of inventions made rotating machines practical and scalable. The electrical generator, which converts mechanical motion into electricity, was first demonstrated by Michael Faraday in the 1830s. A few years later, the first electric motors were built — essentially generators operating in reverse, converting electricity into motion.

Later in the century came the first practical internal combustion engines. Like steam engines and electric motors, they were fundamentally about producing rotational power. By the beginning of the 20th century, there were two viable ways to generate torque at scale: electric motors and internal combustion engines. For transportation, internal combustion engines had a decisive advantage: the vehicle carried its energy source in liquid form. Electric motors required a wired connection to electricity, making it impractical to “plug in” every block or so.

For the next hundred years, internal combustion engines dominated transportation, from automobiles to ocean liners. That dominance is now being challenged by three developments: rapid improvements in battery technology, major advances in electric motor efficiency and control, and the growing realization that burning fossil fuels in vehicles is damaging the planet.

Today, the torque war is increasingly being won by electric vehicles. While not yet universal, many of the practical barriers to adoption have been removed. Recent advances in battery chemistry and charging systems — particularly in China — have demonstrated the ability to add hundreds of kilometers of range in well under ten minutes under optimal conditions, with 70 to 80% charging achieved in roughly 10 to 15 minutes, substantially narrowing the refuelling gap with internal combustion vehicles.³

The most significant advantage of electric vehicles is that they produce no tailpipe greenhouse gas emissions during operation. Of course, they still use electricity, so the climate impact depends on how that electricity is generated. If the grid relies on fossil fuels, emissions are merely shifted upstream rather than eliminated.

For a deeper and more technical look at electric motor technology—and why it matters—we invite you to read our companion article: Stator the Art.

Reading

- Tools, History. “James Watt: The Visionary Engineer Who Launched the Industrial Age - History Tools.” May 26, 2024. https://www.historytools.org/stories/james-watt-the-visionary-engineer-who-launched-the-industrial-age.

- Faraday, M. Experimental Researches in Electricity. Royal Society of London, 1832. http://archive.org/details/philtrans01461252.

- Weng, Jingwen, Andreas Jossen, Anna Stefanopoulou, Ju Li, Xuning Feng, and Gregory Offer. “Fast-Charging Lithium-Ion Batteries Require a Systems Engineering Approach.” Nature Energy 10, no. 11 (2025): 1289–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-025-01813-w.