The Long Way Home

When a beloved species moves back from near-extinction, we feel joy. But this is the Anthropocene, when many more species are threatened than are saved every year. Part 1 in a series on extinction.

Rebirth is emotionally and culturally powerful

In The Lord of the Rings, deep within the underground land of Moria, Gandalf stands fast upon a stone arch to block the passage of the demonesque Balrog so the Fellowship can escape. But Gandalf is forced to destroy the arch, even as he stands upon it, so together he and the Balrog fall into an abyss. After they fight for days, both are killed. Gandalf is resurrected, and, more powerful and more pure, returns to lead the Fellowship once again. For many readers, Gandalf’s return is arguably the most moving scene in the trilogy, a redeeming wave of triumph and strength — a moment of what Tolkien called “eucatastrophe,” where utter defeat becomes rebirth.

Eucatastrophes are prominent in our fiction and in our lives. The hero, assumed dead, returns from war. The spouse, battling cancer, enters remission and has a long and joyful life. Ross Poldark, once thought lost, returns to join the redoubtable Demelza in a fight to protect local workers. We love these moments; they inspire us. They give us hope.

Each year, a few species, thought nearly or entirely lost, recover

Like Gandalf, each year some species return from the abyss. In the real world, the stakes are absolute: existence or extinction. Here are two examples, drawn from social media:

- This month, the wonderfully optimistic website and magazine Positive News featured positive news (what else!) about the green turtle, which has come back from the brink and has been removed from the “endangered” list.1

- SweetLightning recently told the story of Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna, which hadn’t been seen by science since 1961. It was regarded as critically endangered and perhaps extinct, only to be caught on a night camera with the assistance of local observers.2

“Eco-eucatastrophies” (to use Tolkien's coined term to coin a derivative term) are powerful and moving success stories that prove the worth of conservation efforts. Each is a significant step towards a better-managed planet.

They don’t call this the “Anthropocene” for nothing

When a species re-appears we certainly should celebrate. But we must also keep up efforts to preserve and save other species on our list of concern … and that list is long. Largely as a result of human activities on the planet, species are going extinct at an accelerated rate in this, the new geologic age of humanity: the Anthropocene.

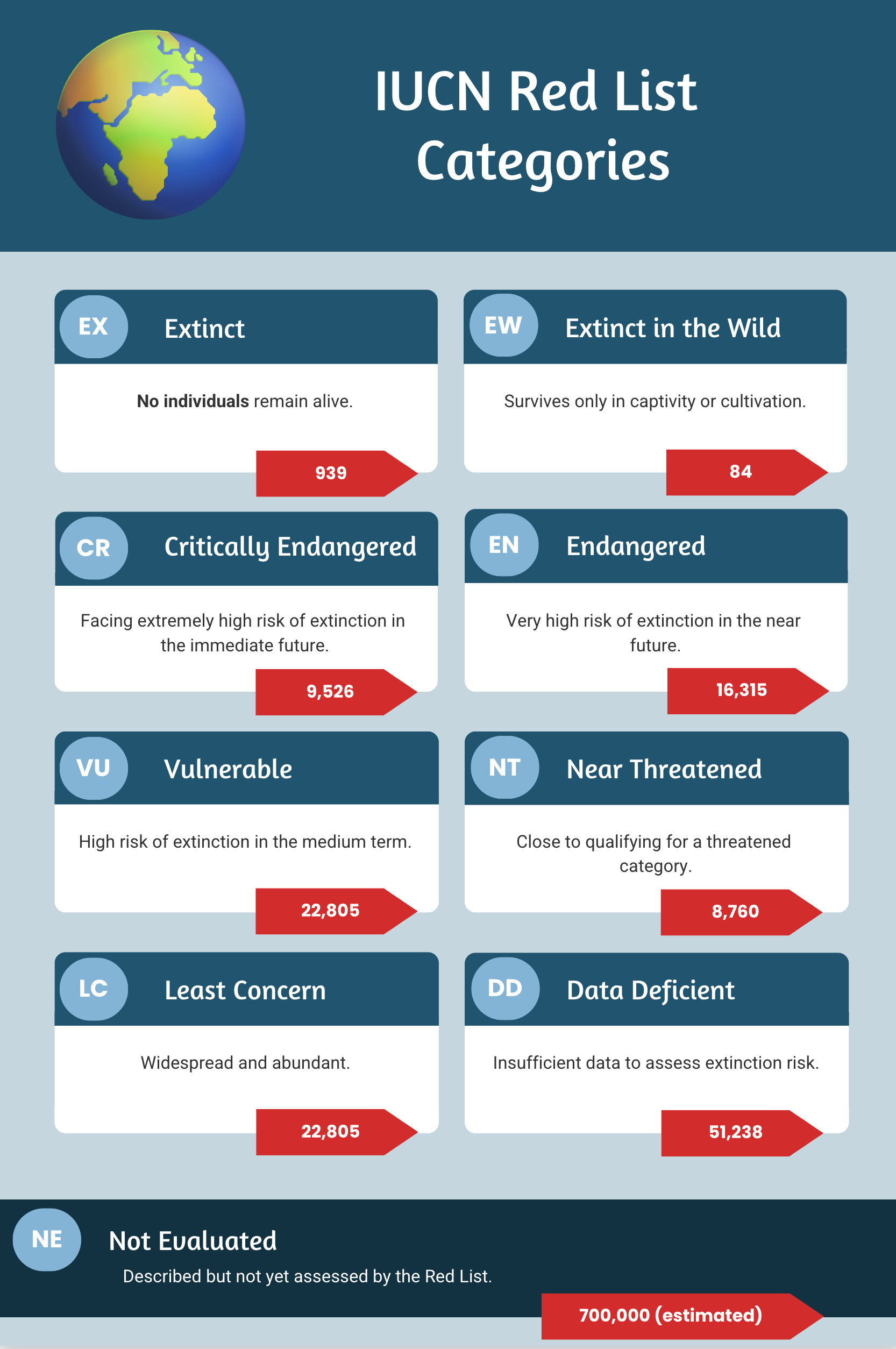

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (usually just called the IUCN) maintains the most-recognized system to catalogue extinction risk: the Red List of Threatened Species.3 The Red List places 172,000 animal and plant species into eight categories. Of these species, 49,669 are vulnerable, endangered, critically endangered,4 only alive in captivity, or thought to be extinct. That's about 28% of all assessed species:

That last bottom line —"Not Evaluated"— is important: in it, the IUCN has listed but not yet appraised another 700,000 (or so) species. But 700,000 species is still only a tiny fraction of the most-well-regarded estimate of the number of species on Earth: about 8.7 million.4

Many species are at risk

You're probably rushing ahead now, wanting to know what 28 percent of 8.7 million is, so you can know how many species are in trouble.

Well, don't do that! Because:

- The 700K list does not evenly represent all groups of living things; the 172,000 evaluated species even less so.

- Scientists have started with important species in their appraisals: charismatic megafauna, vertebrates, corals (because their endangerment is so conspicuous), commercially important invertebrates, and well-studied and important plants.

- Species that are not in the 700K group are often in sheltered or non-obvious contexts: within the soil, the deep ocean, microbial mats, or mycological colonies.

- Extinction does not operate the same way across species or across geologies and microclimates, so the proportions of a small non-random sample will not be representative of the entire 8.7 million.

So how many species are actually in trouble? Nobody really knows. The number is certainly large, though: one of the most-cited estimates puts it at around a million species.5 Others are far higher.

Researchers do agree that the extinction rate, with species disappearing at rates from 100 to 1,000 times higher than historical averages,6, 7 has created a potential biodiversity crisis.

Successes give hope

Crises are difficult to confront, but every problem has to be sized and measured before it can be understood. Even as scientists work to identify at-risk species, we can help. Even as we react to the notion of a million endangered species, we can begin to save them.

We can protect habitat, run recovery programs, reduce threats, and work hard to preserve the species we have put in danger. The IUCN has a great search utility online that lets you explore the status of thousands of species. They have also developed a "Green Status" flag to highlight successes and make recovering species more visible.

Conspicuously, in 2025, we have seen improvements for a couple dozen species, including the peregrine falcon, the Rodrigues warbler, the blue-winged macaw, and the redwing. We have re-established observation of Attenborough's long-beaked echidna, helped the green sea-turtle move from endangered to least concern, and seen improvements for the Shark Bay bandicoot and several land and sea snails. In 2025, the running buffalo clover, the dwarf-flowered heartleaf, South Africa's "baseball plant", and other plants have rebounded, again largely due to conservation efforts.

So you see, it can be done. Even when the way is long, we are doing it.

Reading

- Haines, Gavin. 2025. “What Went Right This Week: The Good News That Matters.” Positive News, October 17. https://www.positive.news/society/good-news-stories-from-week-42-of-2025/.

- SweetLightning. 2025. “Lost, So Small Amid That Dark.” June 21. https://www.sweetlightning.eco/lost-so-small-amid-that-dark/.

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. n.d. “The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.” Accessed October 20, 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

- Gumbs, Rikki, et al. "The status, threats and conservation of Critically Endangered species." Nature Reviews Biodiversity 1, no. 7 (2025): Article 00059.

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES Secretariat, 2019. Accessed October 24, 2025. https://files.ipbes.net/ipbes-web-prod-public-files/inline/files/ipbes_global_assessment_report_summary_for_policymakers.pdf.

- Keck, François, Tianna Peller, Roman Alther, et al. "The global human impact on biodiversity." Nature 628, no. 8019 (2025): 401–409.

- “The Biodiversity Crisis | NatureServe.” 2024. July 30. https://www.natureserve.org/biodiversity.